By Nick Adams MW

A question often asked is what will be the next, new variety that the trade, wine writers and consumers will all be talking about and drinking? And by “new” it doesn’t mean a brand-new creation in a laboratory or through a crossing in a nursery; but a variety that has maybe been under the radar and now comes into view and fashion.

A recent example of this is the Viognier grape – from the Rhône – which is now a firm favourite with many wine drinkers. Some 70 odd years ago almost died out completely but now is wildly planted again in the Rhône as well as a mainstream favourite in many New World countries.

It is estimated that there are potentially up to 10,000 different varieties in the world which technically can make table wine. Of these the Grape & Wine Research Development Corporation records a database of 1,271 being actively used in creating and blending different styles of wine in the world at present.

Of these there are probably 10 which might be described as the most “noble”, well known (by trade and consumer alike) and widely planted – these are often referred to collectively as International Varietals – not least because as the name implies, and their reputations which follow, they are planted around the world. This includes famous names such as:

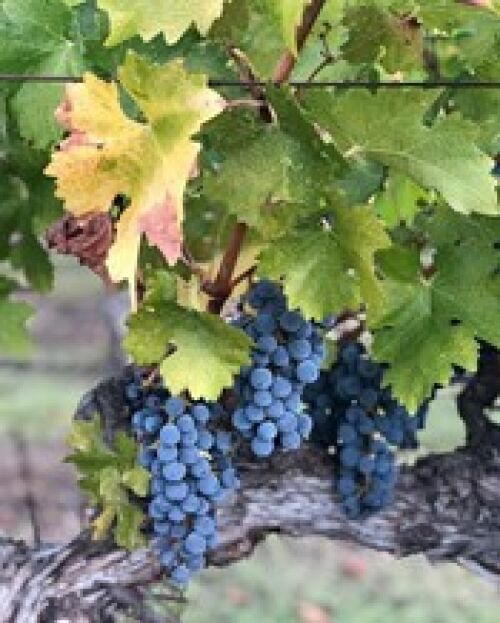

- Cabernet Sauvignon (Image right)

- Chardonnay

- Chenin Blanc

- Grenache (aka Garnacha)

- Merlot

- Pinot Grigio (aka Pinot Gris)

- Pinot Noir

- Riesling

- Sauvignon Blanc

- Syrah (aka Shiraz)

Interestingly though if you look at the Top 10 by the hectares (or acreage) planted then the list is slightly different!

- Cabernet Sauvignon

- Merlot

- Tempranillo – the grape behind Rioja and Ribera del Duero

- Airén (a Spanish workhorse white grape for bulk wine and blends)

- Chardonnay

- Syrah

- Grenache

- Sauvignon Blanc

- Pinot Noir

- Trebbiano (aka Ugni Blanc) – (widely grown in Italy, also in Gascony in France and as one of the component grapes in Cognac and Armagnac)

So, let’s look at some good examples of new, yet to be discovered, and up and coming varieties which would enhance any list – along the way have highlighted some selections from the Peter Graham portfolio.

Starting with Tempranillo which is almost exclusively planted in large areas in Spain, so it is rather specific by country and are is not a “traveller” so to speak – although areas in California, South America and Australia are starting to trial Tempranillo. However, it is also grown in Portugal where it is called Tinta Roriz (used in the Douro as part of the blend for Port wine) and as Aragonez in the south – such as the lovely Alentejo example below.

So, what are the main and most successful indigenous grapes and which ones could be the world stars of tomorrow? The starting point must be Italy and Portugal.

Portugal & Italy

These two countries – apart from certain regions of Eastern Europe – are the champions of their indigenous varieties. Of course, you will still find international grapes planted (Sicily in Italy being an example) but the bedrock of most of their wines is working with local varieties. This is taken to such extremes in parts of Italy that these varieties are almost exclusive to just that province let alone the rest of Italy.

For example, a white winemaker in Gavi Piedmont will work with and champion Cortese, whilst having limited knowledge in his or her counterpart in Soave working with Garganega, whilst another producer in Campania will be focusing on Fiano. Multiply this on the red side and across Italy and you end up with an Aladdin’s Cave of wine flavours and styles which are not only qualitatively strong and interesting but individual and authentic. And then try looking for them on the world stage and who else might be working with these varieties and the short list is … well short. They are the complete antipathy of the term “international”. Likewise for reds there are established varieties such as Barbera in Piedmont and Corvina in Veneto, but it is the south of the country where I think some of the most exciting “new” black grapes can be found such as Primitivo (which is the same as Zinfandel in the USA), Negroamaro and Nero d’Avola. Have a look at the Negroamaro example below from Puglia – Italy’s “heel”.

The same applies to Portugal by region and just to take one high quality example – all ports are made from a complex blend of indigenous Portuguese varieties, led by Touriga Nacional with including Tinta Roriz (Portuguese for Tempranillo out of interest) and Tinta Francesca. A white winemaker in Dão with work with Encruzado, in Bairrada Bical, in Alentejo Arinto and so on. Of all these native whites my vote goes for Arinto with its magical balance between zest and texture with fine stone fruit flavours.

Arinto – Portugal’s finest indigenous white? Stars in the cool Vinho Verde or the warmer Alentejo

And we must highlight some of the star grapes which are behind wines of world class renown including:

Italy

- Nebbiolo – Barolo & Barbaresco

- Sangiovese – Chianti (Classico/Rufina) & Brunello di Montalcino

- Cortese – Valpolicella (Amarone)

- Aglianico – Taurasi

Portugal

- Touriga Nacional – important component in Vintage & Reserve aged Tawny Ports, also full-bodied dry table red wines in the Douro

- Alvarinho – classical Vinho Verde and Monção & Melgaço

- Arinto – Alentejo

- Bical- Barriada

Image Left - Arinto – Portugal’s finest indigenous white? Stars in the cool Vinho Verde or the warmer Alentejo

Site Specific v International?

One of the aspects of these fine native grape varieties is that they may be so site specific that when planted “abroad” they quickly lose their style and identity – something which does not apply to earlier the list of international varieties which maintain a consistent hallmark wherever planted.

I would also be tempted again here to highlight red Rioja (and Ribera del Duero) and its main grape component Tempranillo. Rioja has remained a steadfast UK favourite, but the Tempranillo grape is much less well known or recognised – and maybe again because it doesn’t travel that well – so has become another example of a more “site specific” variety like Nebbiolo with Barolo and Barbaresco.

These are all already established names and recognised wines – although some drinkers may not be always aware of the grapes behind them. But does that matter when maybe the provenance of the wine is more important to the drinker? So, what about the rising stars in other countries and future international favourites?

Maybe one of the most pertinent examples in the last 20 years has been the rise in, and following for, Albariño particularly from Rías Baixas in Galicia northwest Spain. The same grape over the border in the Minho Portugal is called Alvarinho but to date has not made quite the same connection with the drinker, although equally fine. With its fine, crisp citric and stone fruit qualities, unoaked and refreshing style it is clear to see why it has become so popular. But my vote for the new star white grape of Spain must go to Godello – also from Galicia. This grape can deliver then flavours of Viognier and Albariño, with the texture of Chardonnay and the freshness of Arinto.

Image Right - The new star grape? Godello grapes – here ripening in the Valdeorras sun, northwest Spain.

Another example of a grape “on the rise” – as mentioned in the introduction - is the Rhône white variety Viognier – which is now grown successfully across the world and is fully in transition to becoming an international variety. With body and texture akin to a good Chardonnay and precise stone fruit flavours this can be quite a hedonistic burst in the glass when on form.

By contrast the other great white Rhône white grapes – Marsanne and Roussanne are making slower progress in recognition and plantings around the world although top examples comfortably match Viognier for quality. There are pioneers though most notably Tahbilk in Victoria, Australia whose bottled aged museum release Marsanne’s sit under the radar as one of the world’s finer white wines – unoaked with amazing, dried stone fruit qualities and lighter alcohol and fine texture.

Another highly popular wine is Picpoul de Pinet from the Languedoc in southern France, made with the Picpoul or “Piquepoul” grape. This is now a firm UK favourite whose following has grown via its familiarity with the many millions of tourists who visit the region, its distinctive branded bottle shape, and the fact it is a very good and consistent wine with crisp, citric fruits, medium body, and easy drinking style. This wine is now a permanent feature on most restaurant wine lists – wind back just 25 years and few would know of or have featured it.

Paradoxically, there has also been a resurrection of older, traditional European varieties in New World countries – probably the most successful example being Argentina’s success with the old Bordeaux variety Malbec in the Mendoza region. So much so that other countries are now planting Malbec on a large scale and some producers in Bordeaux are replanting it. Another example, if not quite so dramatic, has been Chile’s faith in and success with Carmenère – yet again an old Bordeaux variety (where again it is started to be replanted). I could quite easily see Malbec becoming truly international within a few decades. And whilst we are all familiar now with these South American stars maybe the white Torrontés from Argentina is less so – with its highly perfumed and exotic fruit flavours it is one to consider for your “aromatic” category alongside a Sauvignon Blanc or Riesling. And for red contrast Uruguay has been championing the ancient Southern French red variety Tannat to very good effect – so much so it could well become Uruguay’s “Malbec” in due course.

Some samples of above varieties mentioned...

Another country which teems with indigenous varieties is Greece. Here both long established black and white varieties are now starting to show their paces and building reputations. Highlights include the black grapes Xinomavro and Agiorgitiko and the whites Malagousia and Assyrtiko.

Xinomavro is often referred to as “Greece’s Barolo”, particularly from the Naoussa region in the north where its fine red fruits, firm structure, and floral bouquet touches on the character of it more famous Italian counterpart. The Agiorgitiko is more rounded and plusher with ripe plum flavours especially from the Nemea region.

Assyrtiko has been a long established fine white grape and wine – especially from the island of Santorini where in its dry form it is very crisp, citric, intensely mineral and savoury. And the Vin Santó sweet version (made from sun dried grapes) is one of the world’s greatest dessert wines with its rich toffee and raisin notes balanced by remarkable freshness. Finally, Malagousia – a grape which almost died out – which is quite exotic on style, dry and spicy with ripe stone fruits and a savoury cut. I suppose the yet unanswered question is, are these grapes and wines site specific or could they too by successful when planted around the world given their intrinsic qualities and potential appeal to growers and drinkers alike?

Image Left - The amazing Assyrtiko variety grown here in a wicker basket system on the volcanic soils of the Greek island of Santorini – low grown to counter the strong winds

Austria, Hungary & Eastern Europe

Maybe the most remarkable resurgent in sales and interest in modern times must be the wines of Austria. And this has been achieved mainly through the success and appeal of their native grapes. So much so that the local spicy, citrus Grüner Veltliner variety is as popular in its own way as Albariño is from Spain. And I can see their indigenous reds becoming more successful too. One of the reasons is that many of these make very attractive ultra fruity but low tannins and lighter bodied styles. If you are not familiar with these, I recommend the briary fruit laden, gently tannic Zweigelt (Image right)

One of the oldest Eastern European producers Hungary has a particularly fine indigenous white variety called Furmint. (Image right) It is most famous for Hungary’s luxurious dessert wine Tokaji Aszú but these days the (Tokaj) region is also making vibrant zesty pineapple dry table wine versions. And looking into the future other Eastern European varieties such as examples below may also become more well-known and enjoyed.

Feteasca Neagra – Romania

Kékfrankos/Blaufränkisch – Hungary (also Austria)

Mavrud – Bulgaria

Below is a fine, modern-day example.

And then there are twists to old favourites.

We are familiar with Sauvignon Blanc, but less so with its cousin Sauvignon Gris. With its origin too in and around the Bordeaux region, this grape has interesting and richer textures and a spicy element whilst retaining Sauvignon Blanc’s freshness – and it works well too when incorporated into barrel fermentation. (Image Right)

And to finish if you fancy “something really different” do try the excellent local Norfolk sparkling rosé wine from Flint Vineyards made from an array of unusual cool climate varieties including Solaris (widely grown in Sweden believe it or not), Rondo, Bacchus, Cabernet Cortis and Reichensteiner!

Listing and Selling “Off Piste” Wines on your List

With good preservation systems a good way to trial these wines is By the Glass. This allows you to market the diversity of your list but also to encourage bottle sales from the BTG option. And if sales go well you are assured of a permanent new listing which will work for you commercially as well as aesthetically. Likewise, if sales are disappointing you have firm evidence to drop the wine completely. Think of it along the lines of offering a “Guest Beer”.

On the Main List

Whilst clearly you need to cover all the fashionable styles, grape varieties, and regions of origin in a modern list there is plenty of scope to include a “left field” option and selection without risking any excess cost to the business or confusion for the consumer. If your list is designed and sold by style, then it is quite straightforward to include these in the correct style categories – in fact this nicely encourages people to try something different because it will be linked by style to another wine they already know and enjoy.

If your list is geographically based, then I would encourage you to highlight these more unusual wines in the main heading and promote them by relating them to a mainstream sales style and say “If you like … try this …”

Thankfully, the diversity of grape varieties and the increasing interest in growers and producers wanting to explore and create new styles and flavours is great news for the wine drinker as the vinous canvass seems set to flourish further. Of course, international varieties will always remain strong and sort after but having this mix of offerings could not be better for the wine lover – and helps to create a wine list which will be talked about.