By Nick Adams MW

With (meteorological) summer now here crisp and fruity rosé wines come very much to mind. On a hot summers day there are not many more enjoyable ways of relaxing than with a bottle of rosé wine. These days there is more choice and greater quality than ever before in the category. And I will look at some lovely options from the Peter Graham Wines portfolio.

How are Rosés Made?

As you can see from the bird’s eye picture, left, the description “rosé” is itself a general term – just look at the variation in colours in these eight wines – which are all rosé! This gets right to the heart of the matter as to how you make a rosé wine - you must start out as if you were making a red wine.

When you squeeze a wine grape the juice that runs out is water white in colour – whether the grape you use is black or white. This is because the entire colour is contained in the skins of (black) grapes. Therefore if you want to make a red wine you have to keep the juice and skins in contact with each other. In a simple analogy, it is like making a giant pot of tea where contact between the water and tea leaves produces both the flavour and colour of the beverage.

And the longer you leave the skins in contact the darker the colour becomes. To put this into context, as little as 12 hours will see a “staining” in the wine – after 36 hours – a genuine rosé hue will be achieved – see picture below (if you wanted to make a deep, dark red – by contrast - the contact period could easily be 2 weeks or longer). And then there is the effect of the grape variety itself.

Rosé Wine in the making – now being transferred off the skins to complete fermentation in another tank.

Certain varieties, such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah/Shiraz have much deeper colour pigments in their skins than say Pinot Noir and Grenache. Therefore, Cabernet skins left in contact with their juice for 36 hours will produce, on average, a deeper colour than say Grenache over the same period.

So, the winemaker will judge the moment when they are happy with the depth and hue of the (rosé) colour; at which point they draw off the juice and separate the skins (which no longer are needed). They then finish the fermenting process as though the wine were a white, if that makes sense.

The other benefit of this short skin contact period is that it should help to highlight the fruity flavours and aroma of the wine. In most cases rosés are bottled unoaked leaving their bright fruity character “unplugged” so to speak.

In summary, the most important and popular varieties in the world for rosé wines are:

- Grenache – key grape in the Rhône and south of France/Provence

- Garnacha – the Spanish for Grenache and the most important grape in Spain for Rosado wines

- Tempranillo – the main Rioja grape is being used increasingly in blends for rosado wines

- Cinsault – the number 2 grape in the south of France

- Zinfandel – a hugely popular medium dry style (often called “Blush”) from the USA – mainly California

- Primitivo – from southern Italy – Primitivo is the same grape as Zinfandel in the US. These are usually richer and drier styles

- Pinot Noir – most importantly associated with Rosé Champagne along with the burgeoning English Sparkling Wine market; also used a lot in New Zealand rosés; must be the grape by law in Sancerre rosé; the main grape used in the blend to create Prosecco Rosé (Rosato) in Italy (a few producers use Merlot by the way) and the same principle for Cava Rosé (Rosado)

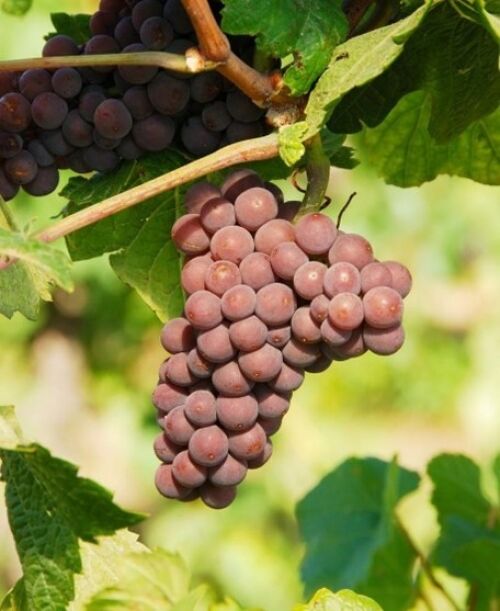

- Pinot Grigio – an interesting twist here as we usually think of Pinot Grigio as a white wine. But the grape is a mutation of Pinot Noir and in its gene pool it still carries some black grape DNA. As it ripens the skins go a coppery colour so if you infuse the juice and skins, you will get a naturally pale rosé colour.

Image left - Ripe Pinot Grigio grapes with their coppery coloured skins.

Rosé Champagne & Sparkling Wines

We all know and enjoy the sparkling side to rosé wines – most famously from Champagne. And here is another anomaly. In the world of wine for still rosé wines it is required by law that they must be made from back grapes where the skins have been in contact with the fermenting juice.

However, in Champagne they are allowed to add a small amount of still red wine (usually Pinot Noir) to the white base wine thereby negating the need for skin contact. This process is also allowed in England and Prosecco (Veneto) in Italy to produce their rosé sparklers. In Spain, though, all rosé Cava must be made by law from direct skin contact with black grapes (again usually Pinot Noir). Of course, producers in Champagne and elsewhere still have the option to sue skin contact to create the rosé colour and many do.

The picture right shows nicely these options at a Champagne House – with the base red wine on the right which could be added to the white base wine on the left. In the middle is an example of a rosé made from skin contact (labelled as “saignée” – or “bleeding” in French)

Whatever the origin or approach, one of the great joys of these wines is usually how fruity they are as well as appealing in their vibrant pink colour.

In Summary …

These days rosés are drunk all the year round, but it is inevitable that sales peak in the hot summer months. They are also a great style for drinking on their own, or with lighter and fresher foods of the season. They work well with most starters for example on a menu; all lighter vegetarian and salad dishes; as well as with shellfish and fish, particularly salmon, sea trout, and tuna. Rosés should be celebrated for their unbridled, uncomplicated and above all refreshing style. Peter Graham Wines have over 50 different still and sparkling examples and I have selected a few personal highlights below – enjoy the summer and raise a glass or two of rosé in the process.