Nick Adams MW blog - Climate Change

I doubt no one is unaware of the recent COP27 Conference in Egypt which reaffirmed that the world is undoubtedly warming up and will continue to warm up exponentially unless significant action is taken. Global temperatures have already risen by 1.1°C since 1880 – and most of that since 1975. If the rise reaches 1.5°C they see this as a “tipping point” in the acceleration of temperatures for the rest of this century. I have attached a link below with the full summary report. Apart form the obvious social and economic ramifications there are significant parochial issues here for the world of wine. How might these increases affect the style and quality of wines from existing regions – both Old and New World - and is it all bad news? And I thought it might then be interesting to recommend some contrasting cool and warmer climate wine examples from the Peter Graham portfolio to finish with.

The highest (shade) temperature I have ever personally “enjoyed” in a vineyard was some years ago in California when we hit 50.1°C in the shade one afternoon – quite an experience for an Englishman abroad. Of course, this was just temporary as we soon were inside in perfectly air-conditioned offices after being out in the winery and vineyards, but it was quite a shock at the time to think that these sorts of temperatures were possible. These are now not uncommon – certainly for levels well into the 40°s - as we all know in Europe from this summer’s record-breaking temperatures and drought conditions.

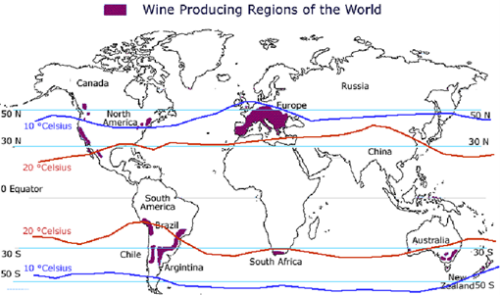

The historically accepted world map of ideal wine growing conditions has long said that the best and most consistent conditions are found between 30-50 latitude north and south of the equator (please see map). But with climate change is that all set to change?

Even if the vine survives when it becomes too hot the plant simply shuts down (to survive) – water and sugars are reversed away from the grapes to the trunk and root system for it to remain hydrated. Despite very warm temperatures the grapes fail to ripen and start to desiccate into raisins. (see right image) Chlorophyll levels drop, and eventually the crop is ruined even if the plant survives the assault. In addition, the vine may be weakened overall so the next growing season’s production can also be badly affected, even if that year’s temperatures as more moderate.

And with global warming this is only set to exacerbate. But is it all bad news for all growers?

Ironically some growers may benefit as they move from highly marginal climates to warmer (not hot, hot) and more consistent growing conditions - and this potentially includes England. Early days but many English wine producers are saying that 2022 was their best harvest. To quote just one example from winemaker Tommy Grimshaw at Langham Wine Estate in Dorset – who had a bumper crop in 2022:

“This year we have reached amazing levels of ripeness from a large yield. A longer growing season meant that our grapes have had longer “hang time” to build up the all important phenolic ripeness, which leads to wonderful fruit character”.

A Burgundy producer based in Beaune recently told me that the effect of global warming has meant that his coolest sites on the northern edge of the Appellation are now ripening much earlier and more consistently than he ever remembers (and his experience in Beaune goes back some 25 years) – and every year Pinot Noir grapes are being harvested with increasing levels of ripeness, sugar, and flavour.

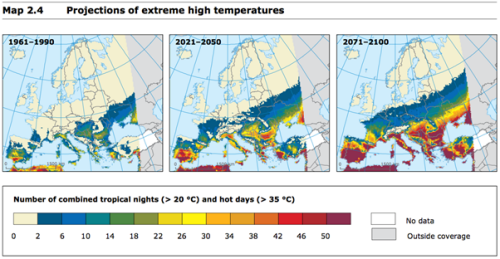

If you look at the projected weather and temperature chart (left) for Europe over the next 80 years, there is unprecedented evidence that areas once defined as “moderate” will become continental and those termed marginal will become moderate in vine growing terms. But those already defined as continental may simply become too hot to grow grapes that make a quality and above all balanced wine. And the problem for our friend in Beaune is that varieties like Pinot Noir are highly susceptible to temperature rises – by that they only make good wine in marginal and moderate climates – not hot.

The problem for the New World may potentially be even more serious. The New World – which is predominantly defined as all countries in the Southern Hemisphere plus North America – are already significantly warmer on average than the Old World. This is partly down in the southern hemisphere to the fact that the Ozone layer is thinner so ultraviolet light intensity is stronger – and this aspect is not solely dependent on temperature either. Average summer temperatures can easily be up to 5°C greater than in their European counterparts. As a result, the grapes simply get riper all things being equal. We all know from drinking New World wine how much juicier, or riper, and fuller bodied the wines from these countries can be versus their counterpart styles and grapes grown in the Old World. This may not be a bad thing if you like that style of course and does not mean they are inferior. You, as a drinker, may prefer these over the leaner and higher acid counterpart examples in the Old World. However, if the Ozone layer thins further and temperatures rise anyway these wines may become, in general, increasingly higher in alcohol and more unbalanced.

But it is not all gloom and doom of course – there is still time for mankind to refocus efforts to moderate the worst excesses of climate change and growers will adapt so that areas once deemed unsuitable for the consistent growing and harvesting of grapes become commercially viable. Chatting recently with Sam Lambson of Minimalist Wines (South Africa) he said that a few years ago he realised that the cooler (white grape growing area) of Elgin was going to warm up to the point where varieties such as Syrah would prosper – and put his money where his mouth was and started planting the variety.

The reason why this is significant is that all black grapes (which make red wine) require more heat and a longer hang time to ripen fully versus white grape varieties – maybe up to 2-3 weeks longer. Therefore, in cooler climates you tend to find plantings skew towards white varieties and vice versa in warmer regions.

Existing producers may also adapt – if laws allow – and start planting varieties which enjoy and do better in warmer climates. Marc Perrin, one of the co-owners of Château de Beaucastel, in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, told me that a) global warming had unquestionably affected their vineyards, growing seasons and harvesting regimes and b) that even Grenache (normally a variety that enjoys the heat) was starting to struggle some years with the temperatures, but Mourvèdre (an important part of the Beaucastel blend) adapted much better to higher temperatures, so its proportion in the blend may well increase in the coming years.

An interesting and very practical example, but this issue also comes with a threat to tradition, a producer’s established style, typicity and the whole concept of what the French term terroir. This is a genuine worry in Burgundy for example where Pinot Noir is especially sensitive to rises in temperature and its whole style – or what we might call generically “red Burgundy” - may well change consistently overtime. But only time will tell, but one thing is for certain - vine growing, and winemaking are set to change, and producers will need to rethink about varieties grown, where they are planted, canopy management, harvest dates and wine styling more than ever before.

(Image Right:Sam Lambson – Minimalist Wines – now growing Syrah vines (and making Syrah wine), in Elgin – historically a white grape region in South Africa)

Let’s finish with a nice cross reference example of a white and red made in the Old World (France) and New World (Australia) to see the style and origin differences when still using the same grape but also how the climate they have been grown in has affected the style. I love this sort of tasting comparison which showcases how good both Old World and New World wines can be when based on the same model. Do try these two excellent Syrah/Shiraz – one a classic French, relatively cooler climate, North Rhône Crozes-Hermitage from Domaine Chevalier and a classic, warmer climate, Barossa Valley Shiraz, Australia from Yalumba

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/20-crozes-hermitage-les-voleyses

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/19-yalumba-wild-ferment-barossa-shiraz

And then two Chardonnays. This grape is seen by many as one of the most adaptable to climate differences of all white varieties – with its style very much reflecting the warmth of the growing area. Lovely contrast here between a classic cooler climate Chablis from Domaine de la Motte and a riper, richer style from the new wave growing area of Tasmania, from Dalrymple Winery

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/20-chablis-domaine-de-la-motte

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/17-chardonnay-cave-block-dalrymple