It has been interesting to hear from several trade clients in recent times – and not least when I was running some WSET courses with PGW customers recently - about the subject of general misunderstandings and misnomers in and about wine which have not only evolved over the years but, in some cases, have become hardened into fact.

In some cases, they said that it had led to tricky situations with customers. So, it gave me the idea to look at some of these and advise about the issues in each case, which may also be useful to use to relay to your staff, who are clearly at the sharp end with customers. And along the way I will also highlight some fine wine examples from the PGW portfolio.

In broad summary, in many of these cases I am afraid to report that these “facts” are - in fact – false.

The reason to highlight these is not in any way to be condescending to people because a number have taken shape through (on the surface) logical impressions but ultimately wrong turns in thinking and analysis. In no order the following are particularly prevalent to this day.

The wine is corked

A genuinely corked bottle of wine is one which has become contaminated with trichloroanisole – or TCA for short - formed by a reaction from naturally occurring fungi which live in the bark of trees used to make natural corks. In most cases this organism is eradicated during the process of making corks but sometimes it survives this processing buried within the internal channels in the bark (called lenticels). It is harmless but imparts an unpleasant “musty” or “damp cardboard” smell and flavour to the wine – in the process strips out the fruit character and flavours in the wine. It can be found in varying levels in an affected wine, but badly corked examples are unmissable and singularly unattractive. But I must stress it is only found in wines sealed with a natural cork – not a screwcap, plastic cork, or glass stopper.

Most importantly, a corked wine is definitively not where some cork dust or debris has fallen onto the surface of the wine in the act of drawing the cork out of the bottle. In this instance you just need to scoop out these particles and enjoy the wine.

There’s broken glass in the bottom of the bottle

This relates to – and only visible in white and maybe rosé wines – small crystals that form in wine. They are called Tartrates – formed naturally from the tartaric acid in the wine (one of the main acids in wine) and come out of solution when the wine is chilled. Once formed they do not dissolve back into the wine if it warms up. They also sometimes stick to the underside of a cork if the bottle has been stored on its side for long enough. They are harmless and tasteless, and a good sign that the wine has not been over processed in its making. And there are in red wines too, but you don’t notice them so easily because of the depth of red colour.

They are categorically not fine pieces of broken glass.

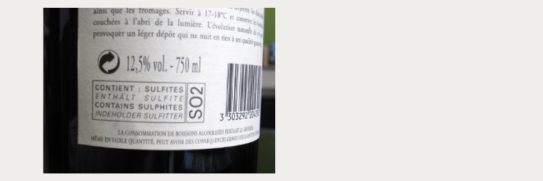

Wine gives me a headache – (caused by the “Sulphides”)?

Sulphides or Sulphites are a naturally occurring biproduct of yeast fermentation in wine. If there is more than 10mg/lt in the finished wine, then – by law – this needs to be indicated to the drinker on the (back) label. Sulphides also form from the addition of Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂) in winemaking and storage. This is an industry wide used antioxidant and antiseptic – and is also used extensively for the same reasons in the food industry.

Levels vary by wines – any wine purporting to be “natural” will have very low levels; red wines tend in general to have lower levels than white wines. Dry wines will have lower levels than sweet wines. But it is also down to the producer – all quality producers will only use what they must (ie bare minimum) to maintain the wine’s stability. Producers of large quantity, bulk wines tend to play safe, and these wines often have higher levels. It cannot be categorically said that Sulphides are not a contributant towards headaches for certain people (ie a mild allergic reaction). According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an estimated 1% of people are indeed sensitive to sulphites, and about 5% of those individuals have asthma as well. So, for a few it can be an issue.

This concern it is not to be taken lightly but it must also be said that consumption of a lot of wine at one time – and especially if not hydrated by water – will certainly give anyone a headache too.

The wine is not clear, it’s hazy and is Out of Condition

Most wines we enjoy are usually brilliantly clear and bright – but a few may indeed not be crystal clear, and in some cases hazy. Is this automatically a problem?

There is a potential fault here which is the wine has thrown a protein haze – you may have noticed that olive oils can do the same thing for example. This won’t affect the flavour but aesthetically is less attractive. I must stress this happens very rarely these days with wine.

What is more likely is that the wine has not been over processed and may well be what is termed as “natural wine”. Although there is not a strict definition of what a natural wine is they are made by producers who believe that wine should not be over processed or clarified and tasted as for what is “naturally” is. This often links in too with people who practice organic and/or biodynamic practices. Once fermentation has completed the wine is cloudy – not least with dead yeast cells – and in most cases wines are clarified with finings and then filtered so that all these particles – referred to as colloids by winemakers - are removed and the wine is bright. Natural winemakers believe that you also risk taking out flavours too, so eschew using finings and filtration. So, fundamentally is a philosophy as well as a winemaking decision.

It does not mean though that the wine is faulty it just won’t be clear. And these are not the only hazy drinks when you think about it – there are bottle fermented hazy beers; cloudy cider; cloudy lemonade. I think these wines should simply be judged on their merits – by that do they taste good!

I am Vegan/Vegetarian - is this wine suitable for me?

This is becoming an increasingly important issue – and I would recommend that you use the symbols Ve and V next to wines on your list that are – PGW have an excellent section in their main wine list to help you identify these – please see PGW links below.

The question revolves around the use of additives which help clear and stabilise a wine prior to bottling. A number of these have an animal base (most classically egg whites) or milk. There are plenty of other options a winemaker can use which makes their wines vegan/vegetarian friendly, so it is worth highlighting and coding these on your list so save time dealing with queries. I must stress that there are no residues left in the finished wine, so the issue is one of principle.

PGW WINES SUITABLE FOR VEGETARIANS

I don’t like any wine made from Chardonnay

I must make it clear right away this is not a criticism of anyone who does not like the Chardonnay grape but an observation from having chatted with people who say they don’t like the grape. When chatting further I find that a significant proportion of them are objecting to the style of the wine rather than just the grape itself. Chardonnay it the most widely planted of all white grape varieties, so it is grown in a lot of places and climates. As a grape variety it is very adaptable and what might be termed climate sensitive – by that if grown in a cool area (the most famous being Chablis in Burgundy) the style is lighter in body, crisper, with more apple and possible citric notes.

Grown in a warm climate (such as many in the New World) it has more tropical fruits, ripe peaches, and is much weightier and fuller bodied. Then add the elements of oak and barrel fermentation, lees aging (giving bready notes) and malolactic (giving diary or buttery notes) the wine can develop a very rich and textural style. This is often the style that people then tell me they don’t like and understandably berate the grape as a result.

I have on occasions, got the same people to then taste a classic Chablis (which by law must be made from 100% Chardonnay) and they have admitted that they like that style. In addition, most Chablis use much less oak (often none) so those who also cite the big “oaky” flavours as another reason for not liking Chardonnay find this style much more to their liking for that simple winemaking adjustment.

I would strongly recommend that if you are selling/marketing your wine list by style and/or grape variety that you highlight this aspect for the drinker. And to example this you may want to look at a classic village Chablis and compare it with a richer, oakier, New World Chardonnay.

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/19-chablis-william-fevre

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/chardonnay-black-label-allan-scott

German wines and Riesling were no good, and I still don’t like them

This last section is a pure crie de cœur from myself – please bear with me. This remains a comment and reaction I come across on a surprisingly regular basis and if I may be direct it is time to move on and rethink about both German wines and its star white grape Riesling (pronounced Rees-ling by the way).

The origin of this conviction goes back in time for many drinkers to when entry level German wines – under brand and origin names including Liebfraümilch, Piesporter, Niersteiner etc – were indeed not very good. But there are three very important points for me from this which need to be made:

- We are going back a long time here, so it tends to be an issue with older wine drinkers who remember those days. The whole German wine industry has moved on by leaps and bounds; quality levels are at an all-time high across all levels

- And very importantly Riesling as a grape was never, ever, used in these cheap old blends – to hit their price points less revered and expensive grapes – such as Kerner and Bacchus – were used in these blends - there wasn’t a drop of Riesling in them, so it is unfair to associate this noble grape variety with those wines of that era

- By contrast, younger wine drinkers do not carry any baggage, and the Riesling grape is now high up on their list of favourite styles

So please allow me my own soap box moment and can I recommend that you try a couple of examples – one a classic modern style, drier, crisp, and citrus German Mosel Riesling from the highly respected house of Raimund Prüm and to contrast a lovely (South) Australian Eden Valley example - dry, citric Riesling from Pewsey Vale.

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/20-riesling-trocken-solitar-prum

https://petergrahamwines.com/p/20-pewsey-vale-riesling

These are modern wines in every sense – relatively low in alcohol, unoaked, crisp, and refreshing and vibrantly fruity. And these wines work very well indeed with Asian and spicy dishes

Thank you very much for reading this and I hope it helps to set a new perspective on things which are understandably, and potentially, confusing for people and may lead, on some occasions, to an issue. By arming you with information, which you can share with your sales team and customers in situ, you can turn around a potential objection into a positive sale.